Biography

With Paintbrush in Hand

With Paintbrush in Hand

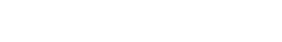

Exhibition catalogue biography of Arthur Sinclair Covey (1877-1960)

Compiled by Pamela S. Thompson. Covey Catalog Editor

“Out of his affection for this particular region of the United States, out of his love for Kansas and Oklahoma soil, in which his first roots were put down, and out of his gratitude to the College where he first began his art study, it was the earnest wish of Arthur Covey that a collection of his paintings find a permanent home here, to honor his life-long friend and first art teacher, Edith Dunlevy.

There paintings are not only the work of his two hands that once held the plow, but they are the reflection of his great soul and spirit. In them, although he has left us in the flesh, he will go on living, so that future generations may know him as well”

--from a biography of Arthur Covey by his wife Lois Lenski

At the tender age of 17, Midwestern-born Arthur Covey declared his hatred of farming in the barnyard with his father’s team and wagon. Throwing the reigns down with a dramatic flourish, he shouted, “I’ll never be a farmer as long as I live!” This dramatic and prescient moment may not have been witnessed by anyone other than the horses and young Covey himself, but it was a decisive and pivotal incident that definitely shaped his future.

Although he was born in Leroy, Illinois on June 13, 1877 and lived much of his professional life on the east coast, the rolling hill towns of Missouri, the flat wheat fields of Kansas and the dusty plains of Oklahoma were deeply rooted in Arthur Covey’s artistic eye. A child of the Midwestern soil, he was the son of a Civil War veteran whose constant wanderlust moved the family around before they landed in Herington, then settled in El Dorado, Kansas until Arthur’s teen years.

The Cherokee Strip Land Run in Oklahoma on Sept. 16, 1893, played a prominent role in his early life—and produced a mental image that stayed with him until his last days. As a 15-year old boy, Covey helped his father and brothers claim and settle three quarter sections of land near Red Rock, Okla. The recollection of that tumultuous, dangerous and calamitous event was so vivid that he pictured them graphically in a lithograph made completely from memory in 1953. “Opening of the Cherokee Strip to Settlement” churns with fallen horses, broken wagons, guns firing, discarded wheels, harnesses, clothing, supplies, even hats left behind on the rough and rugged land.

Growing up between older brother Erwin, sister Carrie and younger brother Floyd, Arthur’s family moved around the endless prairies of Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma, while his father Bryon drifted from job to job. Eventually the peripatetic family moved across Kansas to Herington and then onto El Dorado, Kansas, where Bryon tried the feed business.

Instead of pursuing an agrarian career as his family expected, Arthur Covey’s unlikely path led him to academics and to Winfield. With meager earnings, he enrolled at Southwestern College in 1895 where he studied art under the discerning gaze of art teacher Edith Andrus, who immediately recognized his budding talent. When she acknowledged her student’s amazing forte with a paintbrush and his passion for art, she befriended and counseled him.

Covey gave credit to his first art teacher up until the last days before his death when he wrote:

“In my second spring term at Southwestern, the art teacher, Miss Edith Andrus, later Mrs. R.B. Dunlevy, somehow discovered that I had a talent for drawing and painting, and I joined her indoor and outdoor classes. From then on I had little interest in academic subjects. I made a resolve to be an artist though I had little idea of how an artist set about to make a living. For some mysterious reason, my professor advised me to drop academic work and take up art. Miss Andrus was my chief inspiration.”

With Edith Dunlevy’s blessing, Covey continued to learn and study art in the Art Institute of Chicago where he graduated in 1900 with First Honors; then he used what little savings he had in the bank to fund four years of art education in Europe. First, he studied at the Royal Academy in Munich, Germany, before moving on to England where worked for three years as an assistant to Frank Brangwyn, a notable mural painter, in London. In America, Brangwyn is known for his murals decorating the dome of the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City.

After such a rich, enlightening and productive period working beside a professional mural painter like Brangwyn, Covey was disappointed upon his return to New York City in 1908 as the work he was offered was that of a magazine illustrator . Although this job in commercial art paid the bills, he was not intellectually or artistically stimulated.

His big break came in 1914, when Wichita philanthropist Louise Caldwell Murdock commissioned him to paint a triptych that depicted the themes of Promise, Fruition, and Afterglow for Wichita’s new Carnegie Library. This important commission from the largest city in Kansas most likely launched his career and sealed his reputation as a reliable, creative and successful muralist.

The commission by Mrs. R.C. Murdock for the Wichita library, “Spirit of Kansas,” was the turning point which lead to his acclaim. He spent a year painting the massive three panels that praise the immigrants’ long journey in prairie schooners across the plains; the richness and abundance of the land yielded the afterglow with opportunity for growth, advancement and prosperity.

He was extremely fortunate to be working during the 1920s, when industrial murals, celebrating and glorifying the working man, were widely popular. Also, throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s—considered to be the undisputed heyday of mural paintings—thanks to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) civic-minded, community-wide programs that kept Americans working and producing before the looming war engulfed the country in the 1940s.

After 1915, Covey steadily gained national renown as a mural painter. Remarkably, he continued to receive an unbroken chain of significant commissions for the next five decades.

Covey is also considered to be a pioneer of department store mural and industrial subjects with commissions for a mural at Lord & Taylor in New York and a frieze for Filene’s of Boston. He made use of his Old World observations and drawings from Europe to inspire mural for Lord & Taylor department store.

When plans were made to convert the Wichita Carnegie Library into the Wichita Omnisphere & Science Center in the early 1970s, it was determined the center panel of the three-part mural would have to be destroyed. Before that happened, the mural was purchased from the City of Wichita for $1 by Southwest National Bank. This deal –-or steal as some coined at the time--was brokered by Southwestern College Trustee Mrs. Olive Ann Beech. After repairs and restoration, the mural was installed in the bank at the corner of Douglas and Topeka Streets in 1975 with great downtown community fanfare.

Murals by Arthur were commissioned for many cultural and educational institutions including the Contemporary Arts Building at the New York World’s Fair; the Land Plane Building at La Guardia Airport in New York; the ceiling of the Squibb Building in the heart of NYC; murals for Horace Mann School for Boys in Riverside, N.Y; numerous post offices, schools, libraries and other public buildings in Connecticut and New York; and several corporations and businesses such as Kohler Company of Wisconsin and the Norton Company of Worchester, Massachusetts.

His list of murals includes a 1927 series of images of workers at industries in Toledo, Ohio which were first exhibited in display windows of a Toledo department store, Lasalle & Koch, and seven murals showing foundry workers for the Kohler Company in Sheboygan County, Wisconsin. He was commissioned in 1936 by the Section to paint a mural in the post offices serving Bridgeport and Torrington, Connecticut.

He was also commissioned to paint the patriotic Roosevelt Memorial decorations and the colorful ceiling panels for Trinity Lutheran Church in Worcester, Mass. Some of the residents of Tarpon Springs, FL served as models for the Biblical figures in the ceiling decorations.

Covey was a member of the National Academy of American Water Color Society, the Century Club, and the Salamagundy Club of New York City. He served as president of the National Mural Painter’s Society, vice president of the Architectural League of New York and was elected national academician of the National Academy of Design. He was honored with the coveted Gold Medal of Honor in Painting by the Architectural League in 1925.

While he considered his vocation to be a muralist, Covey is also well known for his easel paintings, both oil and watercolor, as well as prints from his work in the graphic arts. He often considered easel work and printmaking to be his avocation, but despite the seemingly secondary position of this work in relation to his mural painting, he created sensitive and memorable paintings depicting the Midwest, New England and Florida.

He was married to Mary Dorothea Sale from 1908 until her death in 1917. In 1921, Covey married the well-known twentieth century children’s author-artist Lois Lenski (1893-1974) - pictured to the right. He had one daughter, Margaret Covey Chisholm, who was also a painter and muralist; and son Laird Covey with his first wife, and son Stephen Covey with Lenski, whom he met when she was an art student.

Up until 1929, he and Lois lived in and around New York City. But the call to live in the suburbs caused the Covey’s to move to Greenacres in Harwinton, Connecticut. In the winter months, they moved south to their home in Tarpon Springs, Florida.

Between commissions, out of his great love of beauty, he painted many easel paintings, oils, water colors, lithographs, sketches, and etchings. He painted a water color in his Florida studio the day before he died. Lenski said her husband loved Tarpon Springs and his devotion to his semi-tropical adopted home was reflected in his many paintings showcasing the savannah grasses, the trees heavy with Spanish moss, the busy waterfront filled with Greek fishermen and boats of all sizes and shapes.

“Was it the beauty of Nature to which he lived so closely through his childhood years, that gave him the love of beauty that was to steer his course for the sixty coming years of his chosen profession,” asked Lenski, in the 1960 catalogue celebrating the Southwestern College Covey collection.

“No one can say,” Lenski wrote. “But a driving urge was born in that boy at an early age, an urge to express beauty and to give it to others, an urge that never left him as long as he lived.”

For years, Lenski attempted to understand her husband’s driving ambition against all odds to become an artist. “Vague yearnings had begun to stir within him, planted there perhaps by a mother’s frustrated love of the beautiful, by a father’s constant longing for something better, by frequent changes of environment, by the chance meeting with many kinds of people in all walks of life.”

Covey died in Tarpon Springs, Florida, on Feb. 5, 1960. “He often said that Tarpon Springs was the only place for an artist to live because it was so colorful and the people so friendly,” Lenski said.

Upon his death, his private collection was presented to Southwestern College by his wife, Lois Lenski Covey, who personally came to Winfield to dedicate the collection to his alma mater. The large collection of about 200 pieces, which includes paintings, mural sketches, etchings, lithographs, drawings and watercolors, is visible, accessible and beloved by the entire Southwestern College community. A telling statement from the 1960 catalog: “Mrs. Covey’s enthusiasm and generosity is in itself a memorial to her husband’s memory and talent.”

Additional papers and artwork of Arthur Sinclair Covey, dating from 1882 to 1960, are stored in a collection at the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C.