|

Glass: a Divine-Human Metaphor

The process by which sand passes through fierce heat in a complicated process that produces glass is itself fascinating to me. But even more awe-inspiring is the metaphor available to Christians and other spiritually minded folk in the variety of windows made from glass.

A clear pane of glass is like a saint. God's light can pour through without the impediment of dirt or ego. Yet even a dirty pane can illumine some things. Such a person is not a pain but may be a daily kind of person who unwittingly inspires new confidence in discouraged souls.

Colored glass, as in a kaleidoscope, can have what appears to be intrinsic beauty. Yet it would be dark without the sun or other light source streaming from beyond. A stained glass window's pictures may the stories of saviors and saints, pastoral scenes and children's faces. Another more abstract window can contain a swirling flow of colors that tell a story of their own, or as in the little essay that follows, it can link mysteriously with human stories of passion, cruelty, despair, and never-dying hope.

The Implicit Good News

When life says, "Abandon faith and hope"

By Wallace Gray

John and Charmaine Paulin served as valued consultants on this article. The full article, without the above introduction or illustrations, is to appear shortly in Metanoia, a periodical published in the Czech Republic. Leonard Laws suggested the correlation of the text with a photo of the main window of the First United Methodist Church in Winfield, Kansas. Gary Hanna took the picture.

In the darkest nights of human existence, what enables people to hang on and somehow make it through? "Christian faith," an articulate Christian might answer. That answer is not wrong but needs to be filled out and deepened by what I am here calling, "the implicit gospel." The implicit gospel is constantly preparing the world to hear the more explicit sounds and words of hope in the universal Good News that we Christians refer to as the Gospel. {"Implicit" may mean "implied by" or, as The American Heritage Dictionary (SoftKey International, 1995) puts it, "contained in the nature of something though not readily apparent." "Explicit," by contrast, means plainly observable.}

Love sheds light on living, suffering, and dying. Love will support us when we have the strongest reasons to abandon faith and hope. This truth was borne in on me by a story and a window. The story, though fiction, is true to life, and the window, though just stained glass, is true to the implicit Good News in the story.

The story is Kamal Markandaya's novel Nectar in a Sieve. The first-person narrator of the story is Rukmani, a peasant woman looking back on a life that most middle class Western readers would regard as simply a corridor of horrors.

As the story begins, Rukmani situates us in her position as one who has lived through all these horrors with both faith and hope. The novel's first page gives us little hint of how this is done. Her beloved husband Nathan has recently died. Puli is her adopted child who is no longer a child. As she puts it, he is "the child I clung to who is not mine." He was a reluctant adoptee, for, as she explains, she had to tempt him from his soil to hers. She looks at his hands that have "no fingers, only stubs" and tells us she is "comforted." This statement is somewhat enigmatic, and there are other similar mysteries about the family. Rukmani sheds light simply by telling her amazing story.

Everything that is bad seems to happen to this hopeful woman and her family. The list is too long and depressing to be appropriate for this space. The light it sheds fully shines only at the end of the book-and perhaps not even there, for it glimmers from the first page and is fleshed out in the unfolding story.

Fate hammers the family with drought, wash-away floods and blow-down winds. A vicious gossiper, Kunthi, seduces Rukmani's husband, Nathan, and creates a fiction about Rukmani being unfaithful to him. Kunthi even tries to extort blackmail from each of the marriage partners for betraying the other. Fear, anger, and disillusionment do not overcome the couple's fierce loyalty to each other during this ordeal, nor does the couple wholly give up when one son is killed trying to steal a little so the family can eat nor when two other sons get fired for standing firm in a labor dispute, nor even when a daughter, Ira, turns to prostitution to keep her infant child alive. After the couple learns their daughter has become a harlot, Rukmani comments, "So we got used to her comings and goings, as we got used to so much else." However, one night when Rukmani is just awaking in the predawn darkness, she hears furtive footsteps approaching and mistakes Ira for the gossiper Kunthi. She assumes this vicious woman has come now to steal what little the starving family has to survive on during the three weeks before harvest. In defensive fury she attacks the shadowy figure and too late discovers she has almost killed her own daughter.

Ruinous greed from a moneylender, disappointments in grown children, and broken hopes for refuge in a great city still do not break whatever binds this couple together.

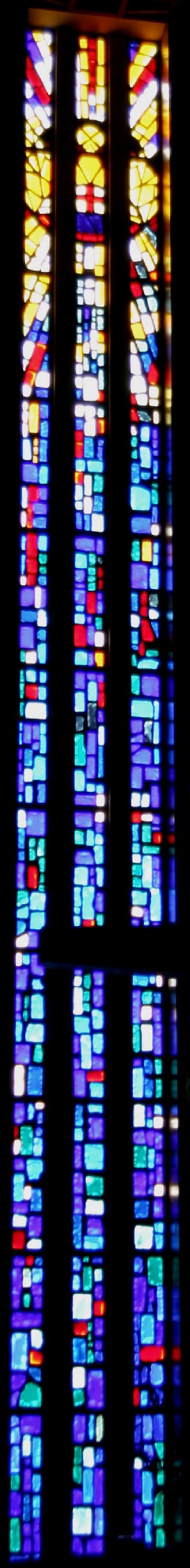

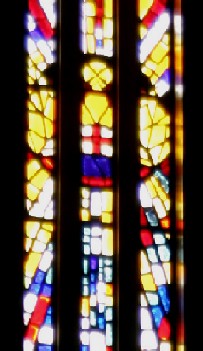

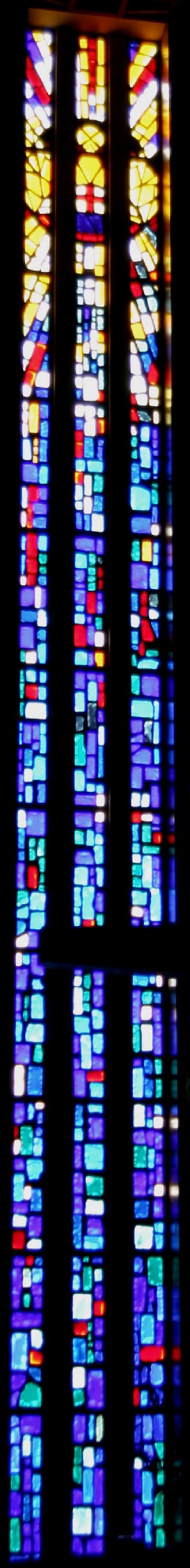

Any such listing as the above is deficient in its lack of the concrete details that the novel supplies, so I turn to the tall and narrow stained-glass window that adorns our church's altar area. It helped me compress all this detail into a few important colors. Miraculously, the colors tell the novel's story in glass. They include the beautiful blues of remembered love and of grinding yet gratifying labor as well as the blues that go on toward a future no one can know and no one can count on. Some of the darker hues can blot out the light of sun and moon. The greens are for love of the land. The reds speak of blood yielded up involuntarily or spontaneously as well as by deliberate, self-giving love. Any of a number of entities may shed blood. Nature is not alone in being "red in tooth and claw." Blood may be shed by enemies, by crime, by war, by injustice, or it may be sacrificially yielded by individuals and groups for each other.

And, finally, the golds . . . . Ah, the golds!

When one's eyes reach the top of the window they find a glorious golden crown, but a cross is inscribed in the crown, as if to say, "No cross, no crown." Some of the darker colors are still glimpsed high in the window, and there are a few lighter touches in its lower, more subdued parts.

Rukmani's story caused me to carefully notice the window that I had looked at many times before. I began to think of parallels between the window and this strange novel, as well as between the novel and the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Such comparativist thinking contains the temptation to ignore the colors of the novel itself. I almost overlooked one passage replete with color in Nectar in a Sieve. It deserves attention in its own right, apart from all comparisons.

Rukmani is recalling a fateful night when she returned to the stone quarry where the impoverished couple had been barely eking out an existence. There she found her ill and undernourished husband Nathan collapsed from labors he could no longer manage but would not give up.

|